Why Dutch Feels Familiar

When I first started learning Dutch, I expected it to be a struggle. Dutch speakers were pretty clear about that: Dutch is very, very difficult. In practice, picking up the basics was surprisingly straightforward.

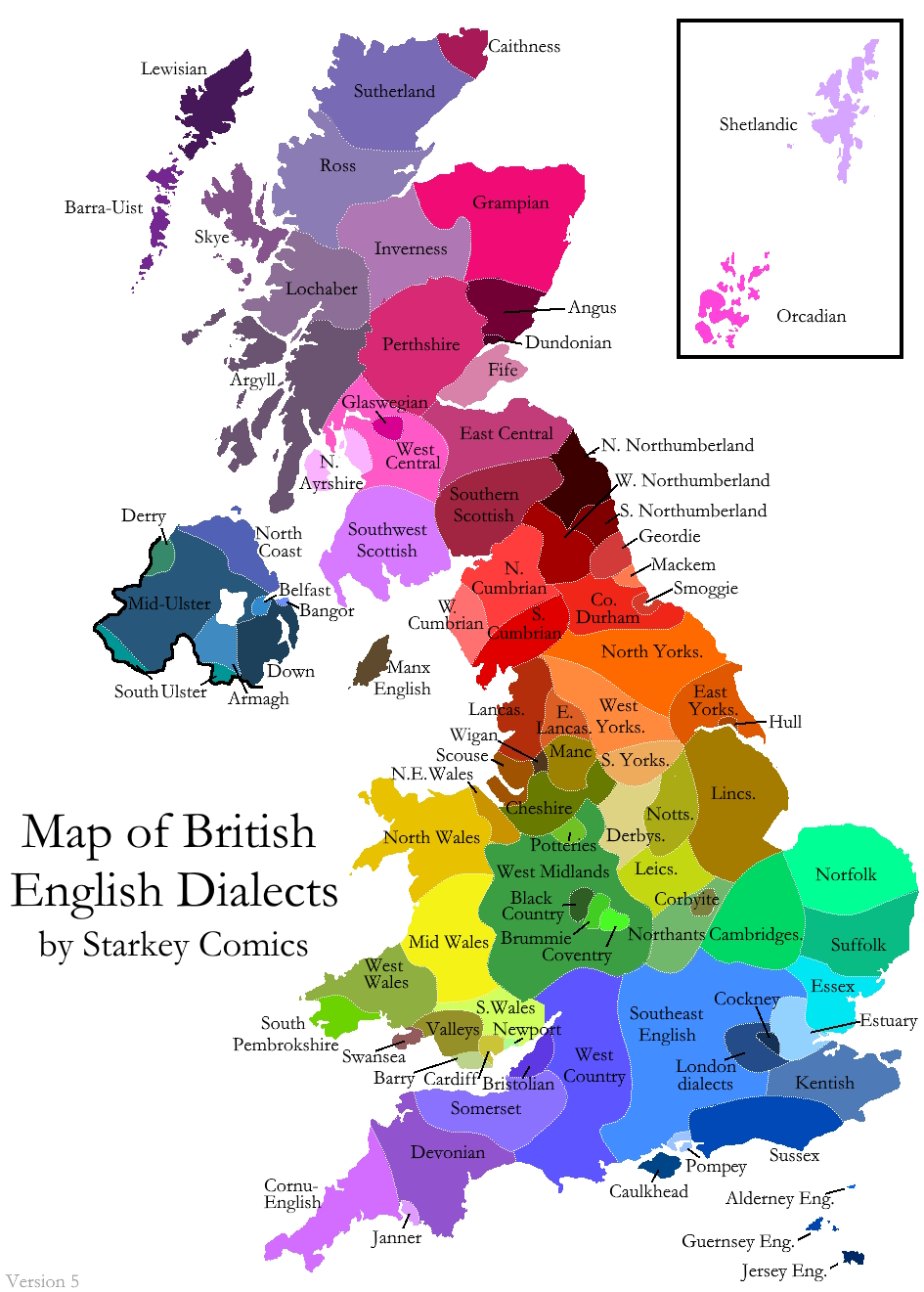

UK dialect map from the wonderful Starkey Comics

That’s almost certainly because Dutch and English are closely related, sharing a common ancestor, proto-West Germanic. During the Middle Ages, regional varieties of this early language drifted apart, eventually becoming separate languages, but many traces of it remain.

That’s why the grammar of Dutch, while sometimes frustrating, often felt familiar to me, and many Dutch words sounded similar or were clearly related to their English equivalents. However, I still seemed to struggle with it even less than the other native English speakers I knew.

This may have something to do with where I'm from. I grew up in the North of Great Britain, which starts in Cheshire and Yorkshire in England and includes Scotland. Although it’s a huge area, and ‘northern’ is definitely a distinct identity, it’s far from homogeneous.

So, more specifically, I’m from the North East, a region that borders Scotland to the north, Yorkshire to the south, and Cumbria to the west and has a long North Sea coast. Even more specifically, I’m from Northumberland, the northernmost county in England.

Because of its location and history, some features of the English spoken in the North, especially near the North East coast, have even more in common with other Germanic languages than the English spoken elsewhere in the country. That’s especially true of the North East’s most widely recognised dialect, Geordie.

Accents and dialects

The UK has an enormous variety of accents and dialects, changing not just from county to county but even from one town to the next.

The accents and dialects of the wider North – from Northumberland through Yorkshire and the North West, and into Scots further north – all share features that are less visible in standard and southern English. Behind this difference is the fact that English didn't develop evenly across Britain. Northern varieties followed a different path from the English spoken in the south, shaped by geography, settlement patterns and influences from other languages.

The accents and dialects of the North East, and especially of Northumberland, share even more of these features. That may be why they’re considered the most difficult to mimic and sometimes even to understand. The Geordie accent can be so strong that the BBC has sometimes had to subtitle or dub it! Like most accents, it’s softened over time, but when I was a child, I was surrounded by people who spoke with very strong accents, like the sheep shearers featured in the TikTok reel below.

Language invasions

Large parts of northern England, and, consequently, its language, were shaped by contact with Old Norse during the Viking period, from the 8th to the 10th centuries. Old Norse and Old English were used side by side here for generations, reinforcing the Germanic features that were already present in Old English.

After the Norman Conquest, French and Latin influence reshaped English, but not to the same degree everywhere. In the south, French quickly became the language of power, law and prestige. But in the North, far from London, that influence was weaker and slower to take hold. As a result, northern English retained more Germanic vocabulary, sound patterns and grammatical structures, particularly in everyday speech. Some of those patterns are still audible today, and speakers of other Germanic languages, especially those spoken in northern Europe, will spot quite a few similarities.

Similar grammar

An obvious example of a Germanic grammatical pattern retained in northern English is the placement of the direct object after the verb without a preposition. For example, where standard English uses “give it to me”, some variants of northern English use “give it me”. The northern version is more direct, mirroring patterns in Dutch (geef het me) and German (gib es mir).

Some dialects of the North use what linguists call the Northern Subject Rule, where the -s ending appears on more verbs than in standard English. You might hear “the birds sings” or “we goes”, echoing an Old Norse influence from the Viking period.

Similar words

The most obvious similarities between Northern European languages and the English of the North can be seen in everyday words:

bairn (child)

Related to Scandinavian barn and Frisian bern. A long-standing northern English and Scots word that preserves an older Germanic term for “child” that has been lost in standard English.

gan / gang (to go)

From Old Norse ganga (“to go, to walk”). Closely aligned with Dutch gaan and related verbs across Germanic languages. Common in northern English dialects and Scots.

yem (home)

From Old Norse heimr, meaning “home”. Closely related to modern Scandinavian forms such as Norwegian hjem and Swedish hem. Still widely used in Geordie expressions like gan yem (“go home”).

ken (to know)

Common in Scots and parts of northern England. Directly related to Dutch kennen and sharing roots in the idea of knowing or recognising.

canny (good, clever, kind)

A quintessentially northern word, also closely linked to ken. In Geordie, it means good, sensible, kind or good-natured.

kirk (church)

From Old Norse kirkja, and still seen in Dutch kerk. Common in Scots and northern English dialects, it was eventually replaced in standard English by church, which was borrowed via Latin from Greek.

gate (street, road)

Still visible in northern English street names, like Stonegate, Coppergate and the delightful Whip-Ma-Whop-Ma-Gate. From Old Norse gata, meaning “street” or “path”, and related to the modern English word gait (a way of walking).

There are also hundreds of Dutch-English cognates that are even more similar (like kat/cat, huis/house and boek/book) and countless English words with Dutch origins.

While these similarities don’t always make Dutch understandable, they do make it feel familiar. When I hear gaan and kennen, it could be that my brain doesn’t have to work as hard as it might for a southern English speaker. And learning Dutch vocabulary lists was surely easier for me than for speakers of non-Germanic languages.

Similar sounds

As well as vocabulary and grammar, northern dialects and accents developed different sounds from southern English. For example, where standard English has wrong, long, and know, Geordie has wrang, lang and knaa, with the vowel often being a bit longer. Southern English pronounces out with a diphthong (a vowel that glides from one sound to another), but many northern English accents use a single vowel sound. So, instead of ‘ah-oot’ or ‘ah-oht’, a Geordie or Scot would simply say ‘oot’. Geordie comedienne Sarah Millican illustrates these sound patterns in a fun (but sweary!) short clip.

The tricky Dutch g/ch was never a problem for me – it’s a feature of the English of the far North.

In Scotland, the ch in loch is produced in a near-identical way and was retained in Scots long after it disappeared from southern English.

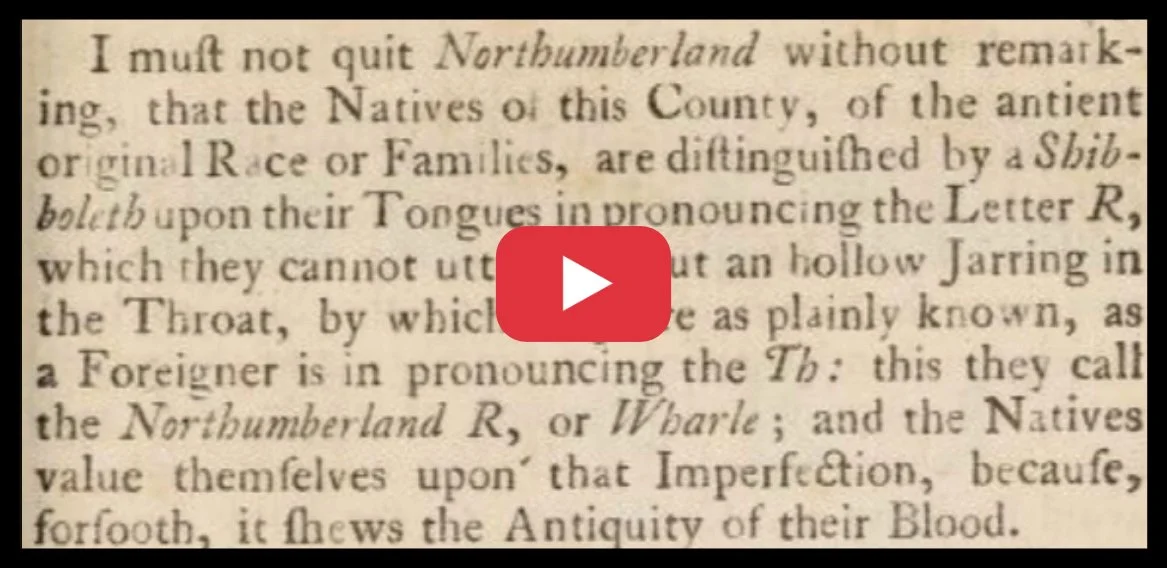

A similar sound, the Northumbrian burr, was used by my grandparents, the last generation to do so. It’s a distinctive uvular r, likely linked to Scandinavian influence, and produced at the back of the mouth like g/ch. This r was also a feature of Pitmatic, which was spoken by hundreds of thousands of coal miners working in pits throughout the North East. The sound was not found anywhere else in the UK, and it is now almost extinct. You can hear examples of the burr in the embedded video.

The Anglo-Frisian link

English has even closer ties with Dutch through a Dutch dialect: Frisian.

Frisian is spoken primarily in the Dutch province of Friesland, although related varieties exist in parts of Germany. It’s the closest surviving relative of English. Both languages descend from a common Anglo-Frisian ancestor that split from other West Germanic languages somewhere around the 5th century. The dialects of the Anglo-Saxons who migrated to Britain and the Frisians who remained in the coastal lowlands were closely related, which is why Old English and Old Frisian shared remarkable similarities.

Some of those similarities can still be seen in modern English. For example, while Dutch uses boter and brood, Frisian has bûter and brea, and of course, in English, it’s butter and bread. A well-known phrase that demonstrates the resemblance is, “Bûter, brea en griene tsiis is goed Ingelsk en goed Frysk,“ which translates to “Butter, bread and green cheese is good English and good Fries.”

Some Frisian words are even more similar to Geordie words, like wetter/wetter for water, fjouwer/fower for four, and kâld/kaad for cold.

After 1,500 years of separate development, modern English and Frisian are no longer mutually intelligible. However, Frisian shows how closely related English and Dutch once were, and how traces of that shared history still surface in modern English – especially in northern varieties, where French and Latin influences had less impact.

What this means for my work

It’s really no wonder that Dutch has always felt comfortable and even beautiful to me. Growing up speaking a variety of English that shares deep roots with the languages of northern Europe has, perhaps, given me a more instinctive feel for Dutch.

This feeling, in tandem with native English, is invaluable in my speciality of creative translation, where it’s vital to create an English text that accurately reflects the tone, voice, mood and sound of the source.

If you need a creative Dutch-to-English translation that resonates with British audiences while staying true to your original message, get in touch.